The veneer revolution

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, one definition of revolution is: “a dramatic and wide-reaching change in attitude”. For decades the porcelain veneer has reigned supreme and the use of other materials for veneering teeth has received little support. Etching of enamel had been demonstrated by Buonocore in the late 1950s, but it was not until as recently as 1982 that Simonsen and Calamia demonstrated that, by etching porcelain with hydrofluoric acid, porcelain could be bonded to enamel with composite resin1.

This discovery led to dentists suddenly being able to transform a patient’s appearance with a relatively minimally invasive technique. Initially there was a debate to whether tooth preparation was necessary but, over time, it was generally accepted that the tooth was prepared before construction of veneers, otherwise the tooth appeared a little over-contoured. Obviously, with a peg-shaped lateral incisor, tooth preparation might be minimal or not necessary. Direct composite veneers have always been part of the dentist’s armamentarium but have been provided as either a provisional restoration or on the grounds of economics.

The preparation of teeth has attracted some controversy. Incisal coverage or removal of contact points are two areas where dentists differ in their approach. In fact, there is a metaphorical fine dividing line between a veneer and a “veneer crown”, depending on one’s point of view, in teeth that have been prepared towards the palatal margin and where the contacts have been removed.

New manufacturing techniques have allowed porcelain veneers to be made extremely thin and so negating the need for tooth preparation in many cases (e.g. Lumineers). Whitening or dental bleaching has concomitantly developed over the past few decades, and has become more predictable. In a large number of cases this should mean that the need for full-mouth veneers is reduced. Sadly, this is not the case and has led to the term “porcelain pornography” being coined by Professor Martin Kelleher2 with regards to unnecessary restorative dentistry being performed to enhance a patient’s appearance.

Furthermore, while on the face of it veneers seem very simple to perform, they are extremely technique sensitive and demanding. Inappropriate case selection, over preparation, over contouring, shade errors and poor execution of bonding techniques are just a few of the problems that have plagued the provision of porcelain veneers.

Composites and bonding techniques have exponentially improved from the original materials developed in the 1960s and 70s. Microfills, hybrids, nano hybrids along with multi-generation bonding agents has meant that both longevity of restorations and aesthetics have improved dramatically. In the past year or so a template system for use with composites has been introduced to the market, the UVeneer (Ultradent). It was developed by dentist Dr Sigal Jacobson3, and has given the clinician more choice when providing definitive veneer restorations. No longer should the automatic choice be porcelain and serious consideration should be given to the UVeneer as an alternative.

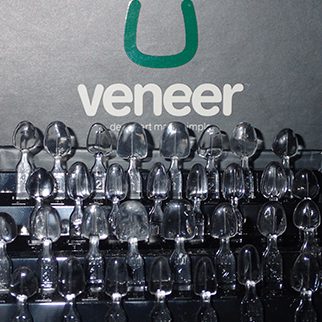

UVeneers are fully autoclaveable plastic templates that are available in two sizes, large and universal (Figure ı). They are arranged in racks, from first premolar to first premolar, for both arches. When used with composite they block out the oxygen inhibited layer, which gives a harder more colour-stable surface with an unrivalled gloss. The advantages and disadvantages of the UVeneer are outlined below:

Advantages

- One visit

- Once mastered, technique is simple and repeatable

- No laboratory costs

- Shade changes easily made as necessary at time of visit

- Only necessary to trim margins and no need to polish

- Enhanced physical properties to outer surface and therefore potentially longer lasting than a direct restoration without a template

- Easily repaired or renewed

- Time?

- Cost to the patients.

Disadvantages

- Multiple units are demanding

- Wear incisally and labially/buccally

- Staining

- Longevity less than porcelain/ceramics?

- Two sizes enough for all cases?

- Patient acceptance as opposed to conventional porcelain/ceramic.

The time element is variable but experience as well as the individual complexity of the case will determine this factor. Given that only one visit is required and there is no temporisation required, the time element may work in favour of the UVeneer when compared to porcelain. The physical properties of composite have improved dramatically since the 1970s, but it would be a bold statement to make that they rival porcelain in all aspects.

With exceptionally large or small teeth the UVeneer is not suitable, but suffice to say it can be used for the vast majority of cases. Multiple units can mean lengthy appointment times, which with porcelain is spread over two appointments. Wear due to abrasion or attrition may occur over prolonged periods and may be a deciding factor in the choice of material.

Clinical technique

A middle-aged female presented with a very white veneer, and wished to have it replaced (Figs 2 and 3). She had no desire to whiten the rest of her teeth but rather wanted the veneer to match her existing teeth. The veneer was removed and the preparation modified. It will be noticed that some veneer cement is still present adhered to the preparation (Fig 4). Air abrasion is utilised and, consequently, the necessity to completely eradicate every vestige of bonding material is negated (Fig 5).

The choice of template is easy to make as for every anterior tooth it is either universal or large. The tooth is etched and bonded in the usual fashion and either metal or clear matrix strips are used to prevent overhangs or bonding to the adjacent teeth (Fig 6). For optimal results, a small amount of flowable composite is placed onto the inner surface of the template chosen (Fig 7). Directly onto the flowable composite a small amount of enamel composite is placed and spread out thinly over the surface of the template, with a flat plastic instrument (Fig 8).

Dentine composite is then applied onto the tooth and spread over the surface, before placing the template directly onto it. The excess is removed with a probe, with care being taken not traumatise the gingiva and cause it to bleed. It is important to ensure excess material is removed, as this will mean quicker and easier finishing later (Fig 9). The tooth is subsequently light cured.

If in any doubt to the health of the gingiva, ideally delay the procedure until this has improved or, at the very least, cure the restoration first before finishing as the margins would be contaminated with blood or gingival exudate. There is also a vertical line on the outer surface of the template to aid the placement vertically on the long axis of the tooth.

- Fig 1 – UVeneer templates arranged in racks

- Fig 2 – A middle-aged lady presented with a very white and unsightly porcelain veneer

- Fig 3 – The patient requested to have the existing veneer replaced

- Fig 4 – Old veneer is removed

- Fig 5 – Air abrasion is used on the labial surface of the tooth

- Fig 6 – Bonding agent is applied to the tooth surface

- Fig 7 – Flowable composite is placed on the inner surface of the UVeneer template

- Fig 8 – A thin layer of enamel composite is then laid upon the flowable composite

- Fig 9 – After applying the dentine composite to the tooth surface, the template is carefully seated before removing excess material

- Fig 10 – After light curing, the template is removed and a finishing bur can then excise any flash at the margin. Care must be taken not to touch the facial surface of the restoration

- Fig 11 – The completed restoration

- Fig 12 – A more natural and aesthetically pleasing veneer

There are many enamel and dentine composite systems on the market and, in this particular case, VOCO Amaris was used, with the added advantage that a highly translucent flowable is available with the system. It is possible to use any flowable composite, as the layer is so thin as to have very little influence on colour. Furthermore, it is possible to use a single shade composite rather than separate dentine and enamel shades as with conventional restorations, but for optimal aesthetics the latter method is preferred.

The template is pulled off the composite after curing (Fig 10) and, after careful cleaning, can be autoclaved and reused. There is no need to polish the facial surface of the finished restoration. A fine finishing diamond bur is all that is required to remove excess restorative material (Figs 11 and 12).

Conclusions

As with any new technique, there is a learning curve and the UVeneer is no different. The UVeneer can be used to provide ‘facings’ for temporary or provisional restorations. If a tooth is lost whether from periodontal disease, trauma or an extraction, the UVeneer can provide aesthetic form to an immediate pontic. There are obviously many other scenarios where the Uveneer might prove useful. Once proficient with the technique, the question whether to use porcelain or a UVeneer and composite becomes a foremost consideration when providing veneers.

About the author

Jeremy Cooper qualified from the London Hospital in 1982 with BDS (Hons). He worked as an associate from 1982-89 in London and the Home Counties. During this time he also held the position of dentist for the Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy.

In 1989 he opened a squat practice in Salford, Manchester where he currently practises. In 1992 he was awarded the Diploma in General Dental Practice from the Royal College of Surgeons.

He has a mixed general practice and, since 2008, has held a challenging position treating patients with alcohol and drug-related problems in a general practice setting.

In 2012, Jeremy was made a Fellow of the International Academy of Dental Facial Esthetics in New York.

He has published numerous articles on a diverse variety of subjects including management issues, dental aesthetics, dental emergencies and restorative dentistry. He is regular contributor on GDPUK and has lectured both in the UK and abroad. He is a member of the BDA and the Faculty of General Dental Practitioners.

He is married to Gill and has three children. His interests range from music, theatre, Manchester United, Jaguar cars and, most important of all, the amber nectar… whisky.

You must be logged in to post a comment.