Anxiety, good and bad

Barbara Gerber explains how a necessary human response can get out of control

Worries, fears and anxieties affect us all; most of the time, our responses to these are reasonable as well as being necessary for survival. In avoiding talking about or acknowledging that we are struggling with anxiety,

we become increasingly more anxious. The purpose of anxiety is to warn us of danger, and to equip us to deal with it and allow us to remain alert until the threat has passed. Therefore, it is a crucial aspect of everyday living. We all need a certain amount of anxiety in order to focus the mind and to help to motivate and protect us.

Imagine you are crossing a busy road and you suddenly notice that a car is speeding towards you. You realise the danger and jump out of the way.

In the example above, a series of physical, mental, and behavioural changes take place, which leads to

the flight, fight or freeze-startle response. This is seen throughout the animal kingdom. The adrenaline hormone and the involuntary nervous system send signals to various parts of the body, enabling it to respond immediately. This is self-preservation in action. When the danger has passed, the changes subside.

The problem arises when the brain misinterprets a situation as being dangerous when in fact it is not; it starts the fight, flight, freeze response which results in a body full of energy raring to go, but with few outlets. When we become over-anxious, worried, or stressed, this interferes with our ability to think clearly and act in a measured way.

Sometimes anxiety can be ongoing, lasting months, even years. Experiencing a number of stresses in our life and becoming preoccupied with worry can result in our everyday level of anxiety gradually increasing. Such long-term anxiety can result in exhaustion, irritability, having difficulty concentrating and can lead to bowel and sleep difficulties, leaving us feeling overwhelmed and low.

Impact on our lives

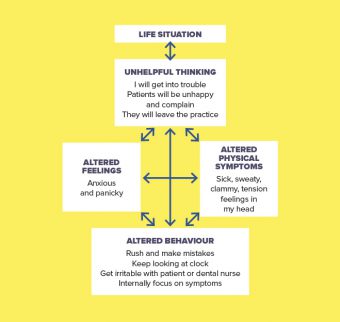

The impact of anxiety on us can be understood by considering the ways it affects different areas of our life. The Five Factor Model examines in detail five important aspects of our lives. These are:

- life situation, relationships and practical problems

- altered thinking

- altered feelings (or emotions or moods)

- altered physical symptoms in our body

- altered behaviour.

Our thoughts about a situation can affect our feelings or emotions, our physical wellbeing, and

our behaviour. We can interrupt this vicious circle

in a number of ways:

- understanding the body’s response when anxious

- challenging your own unhelpful thinking patterns

- challenging your own behaviours.

The most common physical symptoms of anxiety include tight painful chest, difficulty and shortness

of breath, palpitations, trembling, shaking, headaches, nausea, sweating, dry mouth, tight neck and shoulder muscles, tired eyes, difficulties in concentrating, memory lapses and fatigue and these tend to make us worry and often result in withdrawal into self, which in turn starts the vicious cycle. We often indulge in excesses, such as alcohol, food, recreational drugs and cigarettes, which make us feel better short term, but long term, increases anxiety.

What tools can we use to help?

- To help with the physical symptoms we can adopt diaphragmatic breathing. If we have been breathing erratically for some time, it can be difficult to switch from hyperventilating to controlled or diaphragmatic breathing. To practice this, imagine you have a balloon inside your stomach and when you breathe in, you imagine the air going down into your stomach and thus your stomach expands – when you breathe out imagine the balloon deflating and thus your stomach goes in. Take a normal size of breath, because if you breathe too deeply, you will feel light-headed. Breathe slowly and in a controlled manner. It is worth practising daily, starting with lying down, then in a chair, then standing while in a relatively relaxed frame of mind. Being able to consciously change your breathing while anxious is an acquired skill and takes several weeks of practice, but if you are able to master this, you will find it reduces your anxiety within about 30-60 seconds. Alcohol, caffeine and excess sugar increase anxiety, so try to reduce these; however, exercise and relaxation help to reduce anxiety, so try to increase these.

- To help with our thought process: The way we think can contribute to the maintenance of our level of anxiety. We not only think in verbal terms, but also in visual terms. Many people who experience anxiety problems overestimate dangerand underestimate their own ability to cope, e.g. overestimating the problem presented by the patient, and underestimating their ability and skill as a dentist. We anticipate problems based on predicted, extreme outcomes rather than basing them on realistic evidence. One of the problems with anticipation is that the thoughts generated are often inaccurate and fail to relate to actual events. Dwelling on these potentially unpleasant events in detail is time-consuming, distressing, and interferes with daily functioning. Anticipatory worries start with ‘What if…?’ questions. We can also become hypervigilant, seeing danger in every situation. And finally we often hold a post-mortem on situations we have just encountered, ignoring all the positives and only focusing on any perceived negatives. In order to challenge these ways of thinking, we need to focus on the evidence of our own personal experience – thoughts are not facts. We need to look at the thoughts that are making us anxious, e.g. from the example above “I will get into trouble” and ask yourself – Is there evidence to back this up? Has this happened before? And the evidence against – How many times have I been late and not got into trouble? And then come up with a more realistic thought and act accordingly, e.g. “I have been late many times before and nothing bad has happened so I won’t rush”.

- To help to challenge behaviours. The most important behaviour to challenge is avoidance – when we are anxious we often avoid facing up to whatever is anxiety provoking, e.g. not opening mail, not responding to emails, and not making “that phone call”. This only increases your anxiety, so challenge yourself to do whatever you are avoiding.

Author

Barbara Gerber has a BSc and a BA Hons in psychology as well as a diploma in CBT. She set up Equilibria psychotherapy clinic in 2010 along with two colleagues, after having worked for many years at the Priory hospital in Glasgow. This clinic specialises in treating depression, anxiety, low self-esteem along with many others.

Barbara Gerber has a BSc and a BA Hons in psychology as well as a diploma in CBT. She set up Equilibria psychotherapy clinic in 2010 along with two colleagues, after having worked for many years at the Priory hospital in Glasgow. This clinic specialises in treating depression, anxiety, low self-esteem along with many others.

Mental health

Read other articles from this feature

Tags: 2018, Anxiety, Depression, Human response, low self-esteem, Mental health, Psychology, Psychotherapy, Sept, September 2018

You must be logged in to post a comment.